Industrial lighting and the human eye are often misunderstood in factory lighting design.

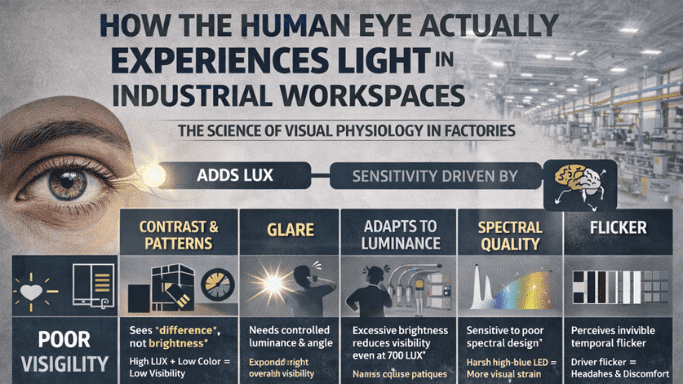

Most industrial environments still rely on a single metric—lux levels—to define lighting quality. When visibility complaints arise, the default response is to add more fixtures, increase wattage, and raise lux values.

Yet factories operating at 500–700 lux still report:

Eye strain

Visual fatigue

Inspection errors

Reduced concentration

Headaches and discomfort

The reason is fundamental:

The human eye does not experience lux. It experiences light as a biological and neurological system.

This article explains how the human eye actually experiences industrial lighting—and why many lighting designs fail when visual physiology is ignored.

The Human Eye Is Not a Light Meter

Lux measures how much light falls on a surface. The human eye, however, is a directional, adaptive, contrast-driven optical system.

Key distinction:

Lux measures surface illumination

Vision depends on how light enters the eye, adapts, contrasts, and is interpreted

The eye continuously evaluates:

Luminance patterns

Contrast ratios

Glare sources

Spectral composition

Spatial uniformity

Temporal stability

This is why two industrial areas with identical lux levels can feel dramatically different to workers.

Retinal Physiology: Rods, Cones, and Industrial Vision

Industrial work depends almost entirely on cone-dominated vision, which is highly sensitive to:

Glare

Contrast loss

Spectral imbalance

Visual adaptation stress

Simply increasing lux does not improve visual performance if these factors are poorly controlled.

Luminance, Not Lux, Governs Visual Perception

The human eye responds to luminance (cd/m²)—not horizontal illuminance.

Poor luminance control leads to:

Frequent pupil contraction and dilation

Retinal fatigue

Reduced contrast sensitivity

Increased cognitive load

A visually comfortable industrial workspace maintains controlled luminance ratios, not excessive brightness.

Contrast Sensitivity – The True Measure of Visibility

Human vision is fundamentally contrast-based, not brightness-based.

In factories:

High lux + low contrast = poor visibility

Moderate lux + high contrast = excellent visibility

This explains why inspection errors occur even in “well-lit” industrial environments.

Glare – The Silent Productivity Killer

No amount of added lux can compensate for glare.

Glare reduces:

Visual acuity

Concentration

Peripheral awareness

And directly increases fatigue and errors.

Visual Adaptation and Lighting Uniformity

Uniformity is not aesthetic—it is a neurological requirement for sustained industrial work. Poor uniformity forces constant visual re-adaptation, accelerating fatigue and reducing precision.

Spectral Quality and Visual Performance

CCT alone does not define visual quality.

Industrial lighting must balance:

Color rendering

Visual comfort

Task accuracy

Duration of exposure

Poor spectral design increases eye strain and defect detection errors.

Flicker and Temporal Instability

Even an invisible flicker stresses the nervous system and reduces hand-eye coordination—especially near rotating machinery.

Peripheral Vision and Industrial Safety

Lighting must support whole-field vision, not just task illumination, to maintain safety and spatial awareness.

Why Traditional Industrial Lighting Design Fails

Most failures occur because designs:

Optimize lux instead of luminance

Ignore glare geometry

Overlook contrast dynamics

Disregard visual physiology

Engineering Lighting for the Human Eye

Human-centric industrial lighting prioritizes:

Controlled luminance distribution

Glare management

High contrast visibility

Stable spectral quality

Uniform visual fields

Flicker-free operation

Conclusion

The human eye does not experience lighting as a number. It experiences patterns, contrasts, stability, and comfort over time. Industrial lighting must be engineered as a visual system, not just an electrical one. Lux is only the starting point.Human vision is the real design target.

Design Lighting for Human Vision, Not Just Lux

If your factory meets lux standards but still struggles with eye strain, errors, or fatigue, the problem isn’t brightness—it’s visual design.

Get a professional industrial lighting assessment based on human visual physiology. Reduce glare, improve contrast, enhance safety, and increase productivity with lighting engineered for the human eye.