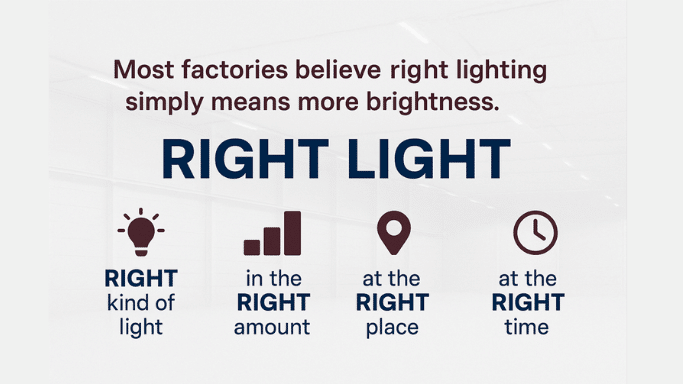

Effective industrial lighting design determines how accurately tasks are performed, how comfortable workers feel, and how efficiently operations run on the factory floor. In most industrial facilities, lighting decisions are still made using a dangerously simplistic assumption:

“If it’s bright enough, it’s good lighting.”

This assumption is not only incorrect — it’s also expensive. Factories that over-light waste energy. Factories that are under-light lose productivity, quality, and safety. And factories that use the wrong kind of light suffer from fatigue, errors, rework, and accidents — even when lux levels appear “adequate.” In industrial environments, lighting is not an electrical activity.

It is a visual engineering discipline that directly influences human performance, process accuracy, and operational efficiency. To address this systematically, global best practice increasingly follows a simple but powerful framework:

RIGHT Lighting = Right kind of light , In the right amount , At the right place, At the right time

This article breaks down this framework in technical detail and explains how it can be applied to real industrial shop floors.

Why “More Brightness” Is the Wrong Goal

Brightness alone is a poor indicator of visual performance.

Human vision depends on:

Contrast, not absolute brightness

Uniformity, not peak lux

Glare control, not wattage

Spectral quality, not color alone

Two shop floors with the same average lux can deliver completely different outcomes in terms of:

Error rates

Visual fatigue

Inspection accuracy

Reaction time

Accident probability

This is why lighting must be engineered, not guessed.

1. Right Kind of Light — Visual Quality Before Quantity

Not all light behaves the same, even if two fixtures deliver identical lumens.

Key Technical Parameters That Matter

a) Correlated Color Temperature (CCT)

Warm white (3000–3500K): comfortable but reduces alertness

Neutral white (4000–4500K): balanced for most industrial tasks

Cool white (5000–6500K): improves alertness but can increase glare if unmanaged

Engineering principle:

Match CCT to task type, not personal preference.

b) Color Rendering Index (CRI)

CRI ≥ 80: acceptable for general operations

CRI ≥ 90: essential for inspection, quality control & colour differentiation

Low CRI causes:

Misidentification of defects

False rejects or missed faults

Increased inspection time

c) Glare Control (UGR / Optics Design)

High luminance sources placed directly in the field of view cause:

Eye strain

Reduced contrast sensitivity

Increased error rates

Glare is a design failure, not a brightness problem.

d) Beam Angle & Light Distribution

Narrow beams create hotspots and shadows

Over-wide beams waste light outside task zones

Optics must be selected based on:

Mounting height

Task geometry

Machine layout

Application Examples

Assembly lines: Neutral white, low glare, controlled vertical illumination

Inspection zones: High CRI, controlled contrast, shadow-managed lighting

Warehouses: Wide, uniform distribution with high vertical illuminance for rack visibility

Wrong light increases fatigue and errors — even when lux levels are high.

2. Right Amount of Light — Lux Must Be Designed, Not Estimated

Lux levels are not arbitrary numbers.

They are defined by standards, task complexity, and visual demand.

Typical Industrial Lux Requirements (Indicative)

General movement areas: 100–200 lux

Assembly work: 300–500 lux

Fine assembly / detailed work: 750–1000 lux

Inspection & quality control: 1000–1500 lux

But average lux alone is meaningless.

Critical Engineering Metrics Beyond Lux

a) Uniformity Ratio (Emin / Eavg)

Poor uniformity causes:

Eye adaptation stress

Frequent refocusing

Reduced task speed

Uniformity is often more important than higher lux.

b) Vertical Illuminance

Humans do not work on horizontal planes alone.

Faces

Control panels

Labels

Vertical machine surfaces

Ignoring vertical illumination leads to poor visibility even when the floor lux is high.

c) Over-Lighting vs Under-Lighting

Over-lighting:

Wastes energy

Increases glare

Accelerates visual fatigue

Under-lighting:

Reduces productivity

Increases errors

Raises accident risk

Engineering goal:

Deliver task-appropriate, uniform illumination, not maximum brightness.

3. Right Place — Light the Task, Not the Ceiling

One of the most common mistakes in factories is confusing fixture placement with task illumination.

Lighting a ceiling does not mean you are lighting the work.

What Determines Correct Placement

Machine geometry

Task height

Worker posture

Movement paths

Shadow-casting elements

Common Design Errors

Fixtures placed symmetrically for aesthetics, not function

Light blocked by cranes, ducts, or tall machines

High-bay fixtures delivering light where no task exists

Ignoring the shadow zones created by the equipment

Correct Engineering Approach

Identify visual task zones

Design lighting to deliver illumination at task height

Control shadow direction and contrast

Ensure vertical and horizontal illumination balance

Correct placement often reduces fixture count while improving visibility.

4. Right Time — Static Lighting in a Dynamic Factory Is a Design Failure

Factories do not operate under constant conditions.

Shifts change

Daylight varies

Processes start and stop

Zones remain idle for hours

Yet many factories run all lights at full output, all day.

This is where controls and automation become essential.

Technologies That Enable “Right Time” Lighting

Occupancy sensors

Daylight sensors

Zonal switching

Dimming controls

Time-based schedules

Integrated lighting automation systems

Benefits of Dynamic Lighting

Reduced energy consumption

Extended luminaire life

Improved visual comfort

Lighting aligned with actual usage

Lighting should respond to operations — not ignore them.

Integrating the Framework — Lighting as a System, Not a Product

The RIGHT framework only works when lighting is treated as a system, not a collection of fixtures.

A proper industrial lighting design process includes:

Site study and task mapping

Standards-based lux planning

Optical selection

Simulation and validation

Control strategy integration

Post-installation verification

Skipping any step compromises performance.

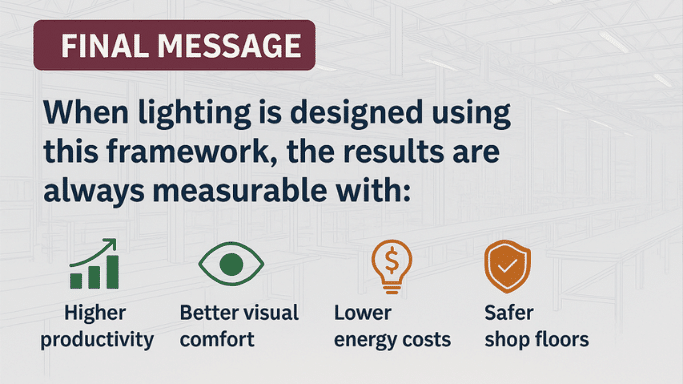

Measurable Outcomes of RIGHT Lighting

Factories that implement lighting using this framework consistently report:

Higher productivity due to reduced visual fatigue

Better quality from improved inspection accuracy

Lower energy costs from optimized lux and controls

Safer shop floors with reduced glare and shadow hazards

Longer equipment life through lower thermal stress

These are not theoretical benefits — they are measurable operational gains.

Final Perspective: Lighting Is an Engineering Decision

Lighting decisions shape:

How people see

How fast they work

How accurately they perform

How safe the environment is

That makes lighting a productivity system, not a utility expense.

Always remember:

Lighting is not an electrical activity – It is a human-centric engineering decision.

Design the light right — and factory performance follows.

Want to know whether your factory lighting is RIGHT — or just bright?

Book a professional lighting assessment and redesign based on task analysis, standards, and real shop-floor data.