A Physiological, Thermodynamic & Environmental Engineering Perspective

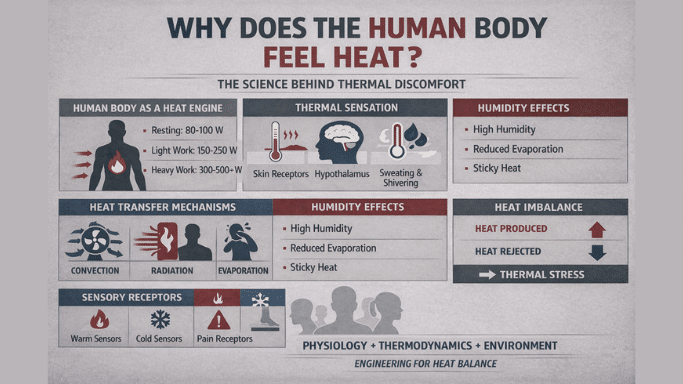

Human heat sensation is not determined by air temperature alone. Instead, it emerges from a complex interaction between human physiology, heat transfer mechanisms, neuro-sensory signalling, and environmental conditions.

This article explains—at a fundamental level—why the human body feels heat, how that sensation is generated, and why cooling strategies fail when they ignore the physics of human thermoregulation.

1. The Human Body as a Heat Engine

The human body functions as a continuous internal heat generator.

Average Metabolic Heat Production

Resting adult: ~70–100 W

Light industrial work: 150–250 W

Heavy manual labor: 300–500+ W

This heat is produced through cellular metabolism, primarily ATP hydrolysis in muscles and organs. To maintain enzyme stability and neurological function, the body must keep its core temperature within a narrow range (36.5–37.5°C).

Any excess heat must be rejected to the environment. When heat rejection becomes inefficient, heat accumulates, leading to discomfort, fatigue, and physiological stress.

2. Human Thermoregulation: The Body’s Control System

Human thermal regulation operates as a closed-loop biological control system:

Sensors: Thermoreceptors in skin and deep tissues

Controller: Hypothalamus (central thermal regulator)

Actuators:

Vasodilation / vasoconstriction

Sweating

Shivering

Behavioral responses (movement, posture, clothing adjustment)

Key Insight:

Thermal discomfort begins at the skin, not the core. The body often feels hot long before core temperature rises.

3. Heat Transfer Mechanisms Governing Thermal Sensation

Human heat exchange occurs through four fundamental modes of heat transfer.

3.1 Conduction (Limited in Air)

Heat transfer through direct contact (floors, chairs, machinery)

Negligible in open air

Significant in seated workstations or contact-heavy industrial tasks

3.2 Convection (Dependent on Air Movement)

Convective heat loss depends on:

Air temperature

Air velocity

Skin–air temperature gradient

Low air velocity: Stagnant boundary layer → poor heat dissipation

High air velocity: Boundary layer disruption → enhanced cooling

This explains why fans improve comfort even when air temperature is high.

3.3 Radiation (The Most Ignored Factor)

Radiant heat exchange occurs between the human body and surrounding surfaces.

Critical fact:

In still air, the human body often exchanges more heat radiatively than convectively. If roofs, walls, or machinery are hot, the body absorbs radiant heat, even when air temperature is moderate.

Real-world implications:

A factory at 32°C with a hot roof feels worse than one at 35°C with insulated surfaces

Shade dramatically improves outdoor thermal comfort

3.4 Evaporation (Sweating Efficiency)

Evaporation becomes the only effective cooling mechanism when air temperature approaches or exceeds skin temperature (~34°C).

Efficiency depends on:

Relative humidity

Air velocity

Skin wettedness

High humidity: Evaporation suppressed

Low airflow: Sweat stagnation

Result: Sweat drips but does not cool, creating intense discomfort.

4. Skin Thermoreceptors: Why Heat Is Felt Locally

The skin contains specialized nerve endings:

Warm receptors: 30–45°C

Cold receptors: 10–35°C

Nociceptors: Extreme temperatures (pain)

Key Characteristics

Uneven distribution across the body

Higher density on face, neck, and chest

Respond rapidly to temperature change (ΔT), not just absolute temperature

This explains:

Why radiant heat on the face feels unbearable

Why sudden airflow gives instant relief

Why discomfort occurs even when air temperature is stable

5. Humidity: The Latent Heat Trap

Humidity does not add heat—it prevents heat removal.

At high relative humidity:

Vapor pressure gradient collapses

Sweat evaporation slows

Latent heat is not extracted

The body continues generating heat, but its primary cooling pathway is blocked.

This creates sensations described as:

“Sticky heat”

“Suffocating”

“Sweating without relief”

6. Metabolic Load vs Environmental Load

Thermal discomfort occurs when:

Heat Produced > Heat Rejected

This imbalance is caused by:

High metabolic activity

Poor ventilation

High radiant temperatures

Low air movement

High humidity

Insulating clothing or PPE

Industrial PPE Effects

Increases thermal resistance

Reduces evaporative cooling

Traps hot microclimates near skin

7. Why Air Temperature Alone Fails as a Comfort Metric

Air temperature is only one variable in thermal comfort.

True human thermal sensation depends on:

Air temperature

Mean radiant temperature

Air velocity

Relative humidity

Metabolic rate

Clothing insulation

This explains why:

24°C air-conditioned spaces can feel hot

32°C warehouses with airflow feel acceptable

Cooling systems fail without airflow or radiation control

Modern comfort models (PMV/PPD, Adaptive Comfort) reflect this multidimensional reality.

8. Psychological and Neural Amplification of Heat

Heat perception is also neurological and psychological.

Factors that amplify discomfort:

Visual glare and bright sunlight

Noise and cognitive stress

Fatigue and dehydration

Lack of environmental control

The brain integrates thermal, visual, auditory, and emotional inputs into a single comfort response.

Conclusion: Heat Is Felt When Physics Defeats Physiology

The human body feels heat when:

Internal heat generation exceeds heat rejection capacity

Heat transfer pathways are restricted or reversed

Sensory receptors detect adverse gradients

The nervous system triggers protective stress responses

True thermal comfort requires integrating physiology, thermodynamics, and environmental engineering—not just lowering air temperature. In industrial environments, designing for human heat balance is the difference between regulatory compliance and real productivity.

Struggling with heat despite air-conditioning?

Real comfort comes from airflow, radiation control, and human-centric thermal engineering — not just lower temperatures. Talk to our experts and design a workplace that actually stays cool.